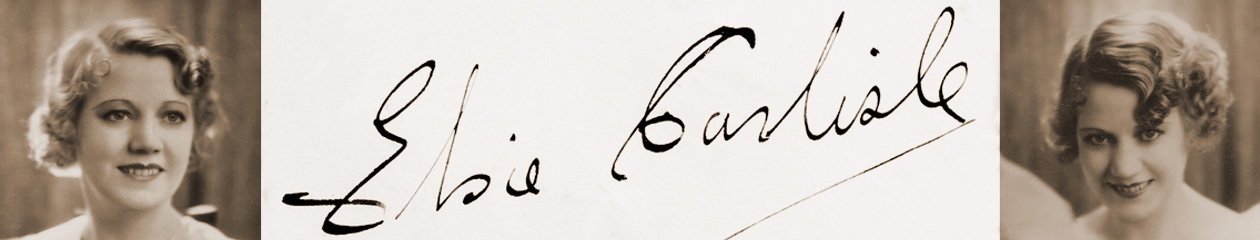

“I’ve Got an Invitation to a Dance.” Words and music by Marty Symes, Al J. Neiburg, and Jerry Levinson (1934). Recorded by Elsie Carlisle with the Embassy [Rhythm] Eight in London on February 15, 1935. Decca F. 5456 mx. GB6978-1.

Personnel: Max Goldberg-t / Lew Davis-tb / Danny Polo-cl / Billy Amstell-ts / Bert Barnes-p / Joe Brannelly-g / Dick Ball-sb / Max Bacon-d

Elsie Carlisle (with The Embassy Rhythm Eight) – “I’ve Got an Invitation to a Dance” (1935)

“I’ve Got an Invitation to a Dance” is the plaintive report of a woman who is reluctant to go to a party that might feature her ex-boyfriend (or possibly even fiancé), accompanied by a new sweetheart. Because she is hopeful for a possible reconciliation, her main concern is to prevent awkward gossip. The focus on idle talk in the context of a breakup might remind us of Elsie Carlisle’s 1933 recordings of “It’s the Talk of the Town,” and in fact that song had the same three composers.1

Elsie imbues the argument of “I’ve Got an Invitation to a Dance” with poignancy while developing a vocal persona strong enough to make up for the vagueness of the lyrics. We do not know, for example, whom the woman blames for the breakup or any of its circumstances. Elsie seems to deliberate over each syllable to reveal what we do know about her character’s motivations, namely her desire to be reunited with her lover.

The melancholy atmosphere is enhanced by the elegant but subdued playing of The Embassy Rhythm Eight (mentioned on the label simply as The Embassy Eight), a studio recording band made up of core members of the Ambrose Orchestra. I should note that on this record (unlike the one with “Whisper Sweet” and “Dancing with My Shadow,” songs for which The Embassy Rhythm Eight almost certainly played the accompaniment), both Elsie Carlisle and the band are credited on the label — a very rare occurrence. Elsie’s records are almost perfectly divided into groups that mention her name and not the band, or that mention the band and not her. Perhaps the Embassy Rhythm Eight, which had been recently formed, wanted the extra publicity.

“I’ve Got an Invitation to a Dance” was recorded in America in 1934 by the Casa Loma Orchestra (with vocalist Kenny Sargent), Hal Kemp and His Orchestra, Paul Pendarvis and His Orchestra (with vocals by Eddie Scope), the Will Osborne Orchestra (with vocals by Will Osborne), Ruth Etting, and A. Ferdinando and His Orchestra.

British versions of “I’ve Got an Invitation to a Dance” were made in 1935 by Roy Fox and His Band (with vocalist Denny Dennis), Billy Cotton and His Band (with vocals by Harold “Chips” Chippendall), Jay Wilbur and His Band (with singer Cyril Grantham), the New Grosvenor House Band (under director Sydney Lipton, with vocalist Gerry Fitzgerald), Lou Preager and His Romano’s Restaurant Dance Orchestra (with vocal refrain by Pat Hyde), and Scott Wood and His Orchestra (in a medley).

Notes:

- In addition to composing “It’s the Talk of the Town” and “I’ve Got an Invitation to a Dance,” Symes, Neiburg, and Levinson also collaborated on the 1935 “Star Gazing,” and Symes wrote the lyrics to “Somebody’s Thinking of You Tonight,” which Elsie would record in 1938. ↩