“Dada, Dada (D-d-d-d-d-d-d-d-da-da)” is a “stuttering song,” a song in which the performer either pretends to stutter or plays around with words that naturally sound a bit like stammering (in the present instance, a young woman’s call to her father — “Dada! Dada!” — serves the purpose). One might think that, in imitating a speech impediment, “Dada, Dada” might risk being insensitive, and yet when one considers every other facet of the song, it is the stuttering that emerges as least offensive. “Dada, Dada” is primarily known for its humorous dramatization of a very innocent young woman being taken advantage of by a somewhat predatory boyfriend. Her cries of “Dada! Dada!” reach her father’s ears, but they only serve to remind him of how he came to have a daughter in the first place; he does not come to the aid of the comically naïve and therefore actually rather unfortunate girl. The primary songwriter, Arthur Le Clerq, was not averse to edgy humor; he would go on to write “Is Izzy Azzy Woz?” (1929) which gives ample opportunities for a singer to practice Yiddishisms, and the overtly ageist “Nobody Loves a Fairy When She’s Forty” (1934).

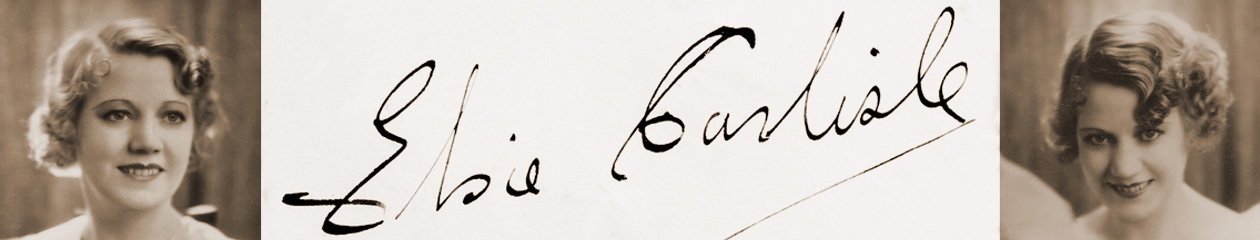

Having admitted that the theme of “Dada, Dada” is fundamentally unwholesome, I must admit that I rather enjoy hearing Elsie Carlisle singing it; her talent for interpreting bawdy, inappropriate lyrics is well known, and the song allows her to show off her upper vocal range by way of adolescent squeaks. A gauge of how much contemporary listeners must have liked her impersonation of a clueless girl is the fact that Elsie recorded it three times in a two-year period.

“Dada, Dada (D-d-d-d-d-d-d-d-da-da).” Words by Arthur Le Clerq and Wallace Dore, music by Arthur Le Clerq (1928). Recorded by Elsie Carlisle with Jay Wilbur and His Orchestra, London, c. December 1928. Dominion A. 43 mx. 1055-2.

Personnel possibly includes Max Goldberg-Bill Shakespeare-t / Tony Thorpe-tb / Laurie Payne-Jimmy Gordon-cl-as-bar / George Clarkson-cl-as-ts / Norman Cole-vn / Billy Thorburn-p / Dave Thomas or Bert Thomas-bj-g / Harry Evans-bb-sb / Jack Kosky-d-chm

Elsie Carlisle – “Dada, Dada” (Dominion; 1928)

In all versions of “Dada, Dada” Elsie alternates between narrating the story and playing its protagonist. In this latter role she is the expert comedian in terms of reenacting the awkward youthful encounter and keeping the mock-stammering from being too implausible or even just annoying and repetitive (for variation she appears to do an imitation of a sort of infantile cuckoo-clock at 1:48). The naughtiness of the lyrics is highlighted by a highly inappropriate reference to Scripture1:

He says I am an angelAnd a heavenly little thing!If angels feel like I do,“Oh death, where is thy sting?”

In this 1928 version, Jay Wilbur’s orchestra shines out admirably even from the asphalt-like shellac of Dominion Records.

Elsie would sing a bit of “Dada, Dada” again with many of the same accompanists in the “Imperial Revels” medley, recorded in late September 1930. She recorded the whole song again the next month, again with Jay Wilbur and His Orchestra (uncredited):

Elsie Carlisle with Jay Wilbur and His Orchestra, London, October 1930. Imperial 2381 mx. 5536-4.

Personnel possibly includes the following: Max Goldberg-Bill Shakespeare-t / Ted Heath or Tony Thorpe-tb / Laurie Payne-Jimmy Gordon-cl-as-bar / George Melachrino-cl-as-vn / George Clarkson-cl-ts / Norman Cole-vn / Billy Thorburn or Pat Dodd-p / Bert Thomas-g / Harry Evans-bb-sb / Jack Kosky-d

Elsie Carlisle – “Dada, Dada” (Imperial; 1930)

The accompaniment on Imperial 2381 is punchier, heavier on the brass and lighter on the strings, and more explicitly comical: the musicians seem to mimic Elsie’s singing at times. Her delivery of the “Dadas” is less sing-song than in her original version and more closely approaches natural speech, if her strange exclamations can be called that. Overall, one gets the impression of performers trying very hard to keep an inherently repetitive piece fresh and succeeding admirably.

Other versions of “Dada, Dada” were recorded in Britain in 1929 by Ray Starita and His Ambassadors’ Band (with vocals by Phil Allen), The Rhythmics (under the direction of Nat Star, with vocalist Tom Barratt), and comedian Jack Morrison (accompanied by Bidgood’s Broadcasters). The full lyrics that Morrison uses depict an increasingly rough struggle between the young people, thus fully realizing the song’s creepy potential.

It should finally be noted that although Elsie Carlisle does speak briefly in a 1933 recording by Maurice Winnick and His Orchestra entitled “Da-Dar-Da-Dar (Da-Dar-Da-Dee),” stuttering the words “d-d-d-darling” and “d-d-d-dearest,” that song concerns the difficulty young lovers have finding privacy — it is a much less troubling piece delivered almost entirely by Sam Browne, and it should not be mistaken for harder stuff.

Notes:

- 1 Corinithians 15:55. ↩