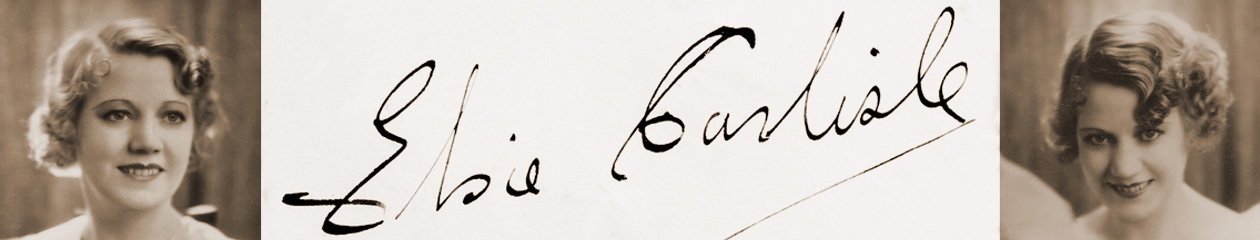

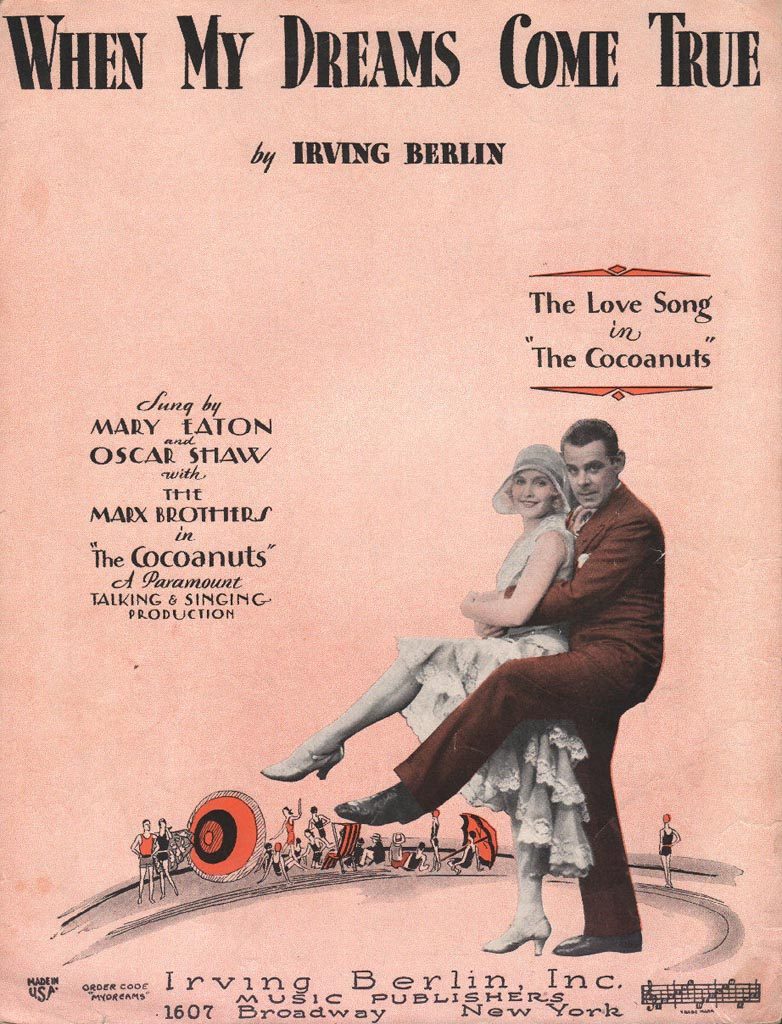

“When My Dreams Come True.” Composed by Irving Berlin for the Marx Brothers film The Cocoanuts (1929). Recorded by Philip Lewis and His Orchestra (a.k.a. the Rhythm Maniacs) under the musical direction of Arthur Lally with vocalist Elsie Carlisle in London on September 14, 1929. Decca F. 1539 mx. DJ49-1.

Personnel: Arthur Lally cl-bas-bsx dir. Sylvester Ahola-t / Danny Polo-cl-as-ss / Johnny Helfer-ts / Claude Ivy-p / Joe Brannelly-g / Max Bacon-d-vib

The Rhythm Maniacs (v. Elsie Carlisle) – “When My Dreams Come True” (1929)

When I first heard The Rhythm Maniacs’ recording of “When My Dreams Come True,”1 it came as quite a surprise: here was Elsie Carlisle singing a vocal part mistakenly attributed to the male singer Maurice Elwin by Rust and Forbes’s British Dance Bands on Record (a.k.a “The Bible”). Indeed, this side has been overlooked by the discographies covering Elsie’s recording career, and Elsie’s role in this Rhythm Maniacs session has been noted in print only by Dick Hill.2

“When My Dreams Come True” is the leitmotiv of Paramount’s 1929 The Cocoanuts, the first Marx Brothers feature. The song is introduced by Oscar Shaw and Mary Eaton but performed throughout by a number of characters (including twice by Harpo, on clarinet and harp). The Cocoanuts is a successful comedy, but it suffers from the awkwardness of other early sound films, which struggled with the novel problem of trying to integrate song-and-dance routines with non-musical material.

Elsie Carlisle’s recording with the Rhythm Maniacs lacks any such awkwardness: she sings with confidence and ebullience, especially when we compare her singing on this record to her excellent but admittedly slightly flawed first session with the same band. In the first takes of “Come On, Baby” and “He’s a Good Man to Have Around,” Elsie even hits a couple of false notes! In contrast, Elsie’s 38-second delivery of the refrain of “When My Dreams Come True” is nearly flawless, and Elsie makes the mental “Spanish castle” of the lyrics sound like an invitingly happy place.

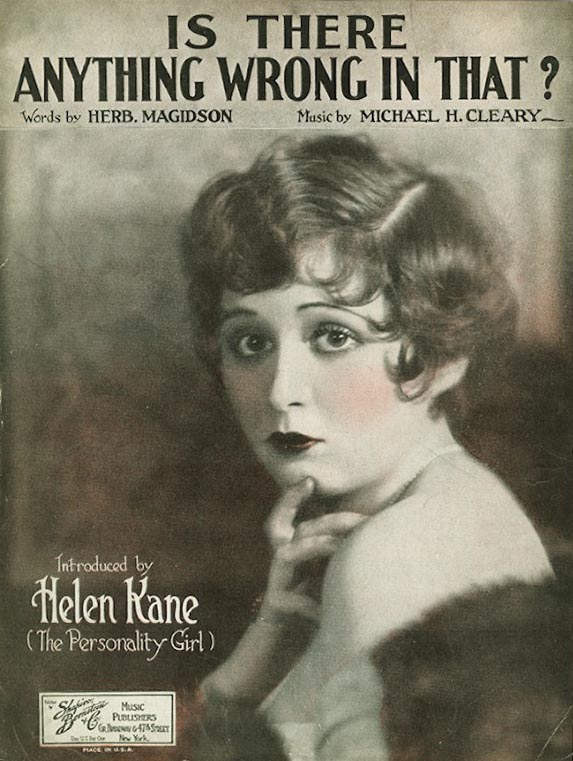

“When My Dreams Come True” was recorded in America in 1929 by Franklyn Baur, Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra (with vocalist Jack Fulton), Hal Kemp and His Orchestra (with vocals by Skinnay Ennis), and Phil Spitalny’s Music (with the Pauli Sisters). It was made popular in Britain in 1929 by Bidgood’s Broadcasters (as Al Benny’s Broadway Boys, with vocalist Cavan O’Connor), The Gilt-Edged Four (with vocals by Norah Blaney), Betty Bolton, and by Stanley Kirkby and Rene Valma. In March 1930 it was recorded by Harry Hudson’s Radio Melody Boys (with vocalist Sam Browne).

Notes:

- On the YouTube channel of David Weavings (a.k.a. “jackpaynefan”), where you may find other rare Elsie Carlisle songs. ↩

- Silvester Ahola: The Gloucester Gabriel, “Discography,” especially pp. 151-155 (Metuchen, New Jersey, 1993). My thanks to John Wright and Barry McCanna for referring me to this fascinating volume. ↩