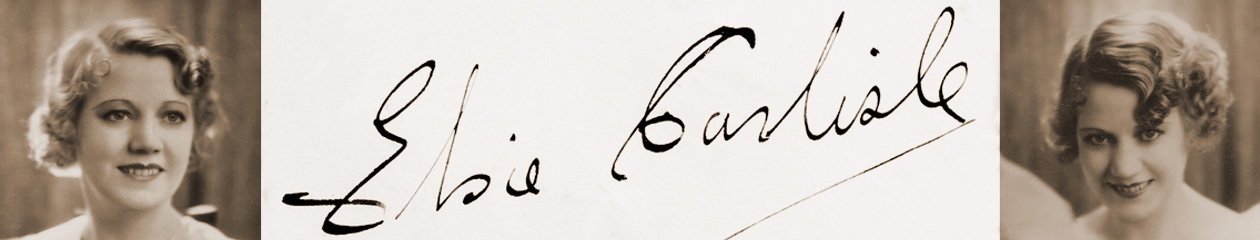

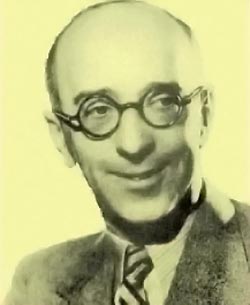

“Oh! Johnny, Oh! Johnny, Oh!” Words by Ed Rose, music by Abe Olman (1917). Recorded by Elsie Carlisle with orchestral accompaniment on February 12, 1940. Rex 9724.

Personnel: Jay Wilbur dir. Alfie Noakes-Harry Owen-t / Bill Mulraney-Bill Boatwright-Joe Cordell-tb / Frank Johnson-Cyril Grantham-cl-as / Sid Phillips-cl-as-bar / Brian Wicks-cl-ts / Bob Busby-p / Jack Simmons-g / Joe Gibson-sb / Tom Webster-d

Elsie Carlisle, Oh! Johnny, Oh! Johnny, Oh!

Transfer by Mick Johnson (YouTube)

“Oh! Johnny, Oh! Johnny, Oh!” is a 1917 composition that has proved itself long-lived, no doubt because it is catchy and because its lyrics have the perennial topic of a young woman’s passionate infatuation as their theme. It is said that Ed Rose wrote the lyrics about two college friends who were absurdly in love; Rose then collaborated with his Tin Pan Alley colleague Abe Olman, who put the words to music. In 1917, Columbia issued a 10-inch disc with Howard Kopp and Frank Banta playing the song on the drum and piano, and there is a Blue Amberol wax cylinder of the Premier Quartet singing it with lyrics altered in light of America’s having entered the First World War; by the end of the song, the Quartet is telling Johnny to enlist: “Go, Johnny! Go, Johnny! Go!”

“Oh! Johnny, Oh! Johnny, Oh!” was revived in November 1939, with recordings by the Andrews Sisters, Dick Robertson and His Orchestra, Orrin Tucker and His Orchestra (with vocalist Bonnie Baker), Benny Goodman and His Orchestra (with vocals by Mildred Bailey, and Glenn Miller (with Marion Hutton), and in January 1940 Ella Fitzgerald would broadcast the song from the Savoy Ballroom. These versions naturally have a lot more swing in them than the 1917 versions, but the renditions are fairly faithful to the original concept, which is to say that they portray a young girl desperately in love in words that are funny and unproblematic.

In her February 1940 version of the song, by contrast, Elsie Carlisle starts out in a state of excitement, whimpers a bit as she describes her feelings for “Johnny” and then continues to ratchet up the effect as the song progresses. Something happens about two minutes into the song when Elsie sings (I should say squeals)

When I sit on your knee,Oh, what you do to me!I justOh, Johnny!No, Johnny!Oh, you have…

Whatever is going on, it appears to lead to talk of marriage, as the song ends with Elsie exclaiming “You’re so full of ideas / For the next fifty years,” along with more “Oh, Johnny”ing. The overall effect is very funny, and Elsie brings out a potential for ribald humor missed by other singers.

Other British versions of “Oh, Johnny! Oh Johnny, Oh!” were recorded in 1939 and 1940 by Jack Hylton and His Orchestra (with singer Dolly Elsie), Joe Loss and His Band (with vocals by Shirley Lenner), Arthur Young and the Hatchet Swingtette (with vocalist Beryl Davis, and Stéphane Grapelli on the violin), Harry Roy’s Tiger Ragamuffins and Phyllis Robins.