Exactly ten years ago — on December 31, 2013, at 7:44 p.m. Pacific Standard Time — I created the Elsie Carlisle page on Facebook. At the time I did not know exactly where my newfound passion would take me. All I had to start with was an earworm.

If you are not familiar with that term, I am sure you are acquainted with the phenomenon it describes. You are exposed to some particularly catchy music, and it resonates so much with you that it is on long-term repeat in your head. It is like an itch, and the only way to scratch it is to play the song again — which of course embeds the earworm even more inextricably in your brain. Sometimes the only way to exorcise an earworm is to become infected with a new one.

So far, what I have described would appear to be an experience familiar to most people, but I seem to fall into a smaller subspecies: people who take pleasure from hearing a good song played repeatedly — twenty to forty times in a row. It has to be the right song, of course, but for a few of us there does not appear to be too much of a good thing. I am happy to say that my peculiar taste in music repetition has not driven people away from me — rather, it would appear that the similarly afflicted are drawn to each other.

I remember, when I was a postgraduate in Cambridge, playing Mary Martin singing “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” (with Eddy Duchin’s orchestra) at least thirty times in a row one evening. But I must have had five friends over, and they all seemed just as dedicated to hearing it played again and again as I did — I am sure I let people take turns hitting the “previous track” button. We reconvened regularly, no doubt to enjoy the collective pleasure of hearing the song for the hundredth time.

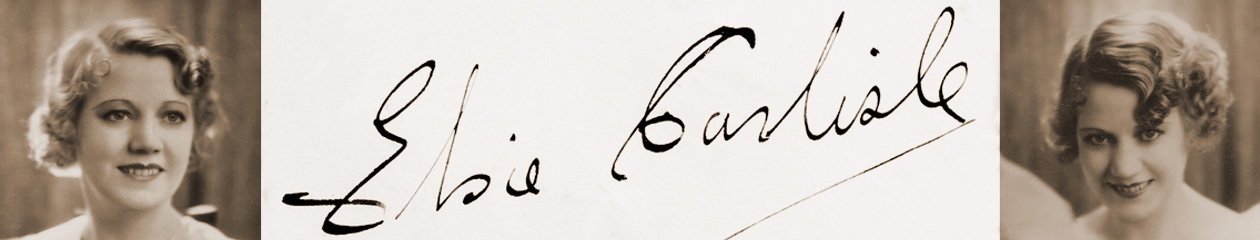

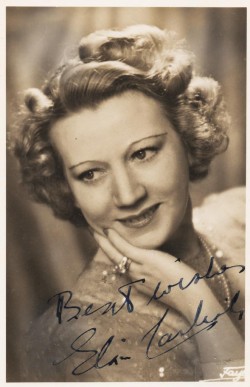

Many years later, in late 2013, my earworm was Elsie Carlisle’s 1930 “Exactly Like You.” After a month of listening to the song on repeat, I began to branch out and listen to other of her hits, such as “The Clouds Will Soon Roll By” and “You’ve Got Me Crying Again.” I grew more and more intrigued. This was my favorite singer — ever. But there were not really that many of her songs available to the casual (or even fanatical) listener at the time — a handful were available in easily obtained digital collections. I did not really know what I was getting into, but I made it perhaps my only New Year’s resolution ever to start a Facebook page for Elsie Carlisle and to learn as I went along how to find out more about her and how to share my appreciation of her art.

January 28, 2014 was the first time I celebrated Elsie Carlisle’s birthday. I descended upon the Facebook groups The Golden Age of British Dance Bands and Female Singers (I would soon afterwards become an administrator of the latter) and spent well over twenty-four hours sharing favorite songs and making new friends — most of whom I have gotten to know much better in the years since. I was impressed by their knowledge of interwar music, as well as of the technical aspects of playing and digitally transferring shellac 78 rpm discs.

The discs began to arrive in the mail, mostly from England, mostly from eBay. There were lovely autographed photographs and postcards, too. I was fortunate to have begun collecting in 2014, as a lot of records and memorabilia were for sale at that time which I have seldom seen since.

Meanwhile, it seemed as if in time, there might be things worth saying about Elsie Carlisle’s songs or periods of her life that would be better consigned to a more permanent and accessible part of the Internet than a mere Facebook page, so in early February 2014 I launched this blog, elsiecarlisle.com, and I began to use it as a place to play around with writing primarily about individual songs, with the occasional biographical piece here and there.

As I grew more comfortable doing digital transfers — which can be extraordinarily challenging, especially when you’re dealing with a 1930s Imperial with uncommonly wide grooves, or an earlier Dominion which was described as sounding merely “OK” by the reviewers when it was new, before it had been scraped a hundred times by steel needles — I started to upload to my own YouTube account. Over the years, I have uploaded some things that I was particularly proud of, especially “What Is This Thing Called Love?” — a song introduced originally by Elsie Carlisle on stage at Cole Porter’s request. Collectors can estimate how scarce that record is.

The years went by, and the blog grew. I was asked to write a few articles on Elsie Carlisle for Discographer Magazine (now unfortunately defunct). But it was really with the beginning of the pandemic that my activities exploded. Stuck at home and with extra time on my hands, I resolved to address the need for a new Elsie Carlisle discography.

When I had started, I had no complete discography to work with. I had Ross Laird’s admirable 1995 Moanin’ Low, which attempts to tabulate all popular female vocalist recordings up through 1933 — but Elsie Carlisle continued recording through 1942 (as I would eventually discover). A helpful person shared Edward Walker’s 1974 Elsie Carlisle — With a Different Style with me. It was groundbreaking when it came out — and still useful — and yet, with the passage of so much time, its incompleteness and inaccuracy are fairly obvious. It took me years to find a copy of Richard Johnson’s 1994 Elsie Carlisle with a Different Style, which remains unsurpassed in its attempts to nail down which instrumentalists might have been present — even at Carlisle’s solo sessions — and yet even it was not complete enough for my purposes. I had developed a discography of my own over time, but I had never shared it. About a month into the pandemic, I published it here as Croonette: An Elsie Carlisle Discography.

I am sure that I am not the only person whose record collection began to grow considerably during the pandemic. In fact, mine was growing so quickly in 2020 that I had to up my game by improving, not just how I transferred records, but how I simply played them — the turntable was spinning nearly all day long at this point. By the summer of 2020, I had released 78curves, a library of equalization curves (and related filters) for playing 78 rpm records through a computer in real time, accurately equalized so as to reproduce the sound of the original performance (as much as possible).

Since then, I have tried to begin replicating my successes on elsiecarlisle.com by launching similar projects involving British vocalists Maurice Elwin (mauriceelwin.com) and Anne Lenner (annelenner.com), both of which are accompanied by biographies and discographies (the Elwin discography, Monarch of the Microphone, being the most daring project yet — I have documented well over 2,000 recordings by Elwin, and I continue to update the 271-page digital tome regularly).

I cannot begin to tell you how many “sidequests” I have had along the way. I have gained more than one client for website design and maintenance because someone admired my sites. And, in order to navigate the filesystems of those websites and efficiently develop and update their various components, I have created a number of free command-line software projects, one of which now has possibly hundreds of thousands of users.

I still have much to do, on this website and on others; much collecting to do; more records to discover and document. But I feel that I can be happy today if I have in any way made Elsie Carlisle’s music more accessible to the non-collector, or if I have had any success in sharing my love of her art.

And may I say what a profound pleasure it has been to make so many hundreds of friends along the way? Even if I am seldom in the same room as you, I feel as if I am always in very good company with music lovers. I hope that our next ten years can be at least as profitable and enjoyable as the last ones.

Happy New Year!

A. G. Kozak